Gloucester Cathedral – Part 2

Reconstruction

Like any monumental building, the cathedral needs extensive repairs from time to time. And like any building of this scale, it struggles with a lack of funds. This is no exception here. Intensive repairs of this landmark of Gloucestershire have been underway for almost four years. As one of the few lucky people, I was allowed to see the ongoing repairs directly from the scaffolding, accompanied by a Polish colleague from Krakow. The last complete renovation of the cathedral took place at the end of the 19th century.

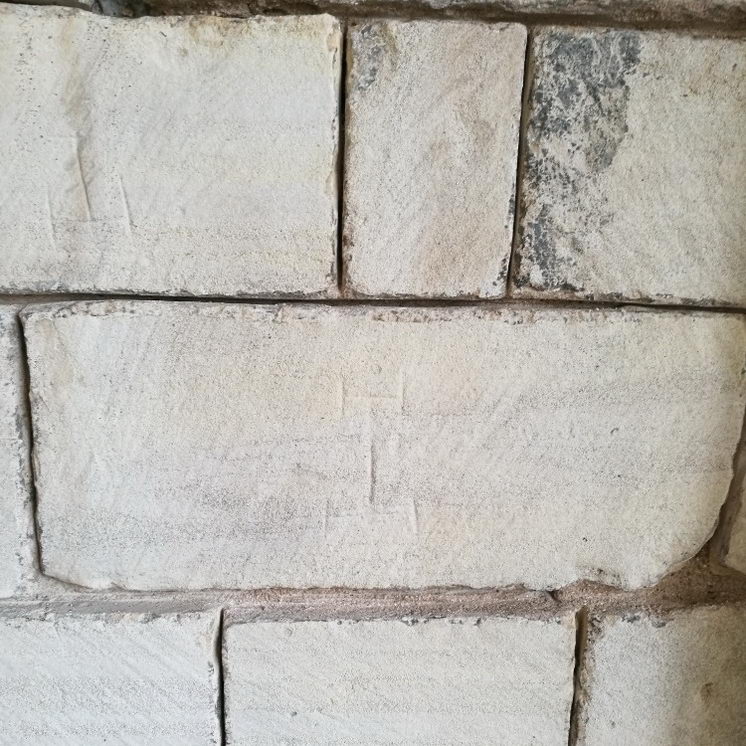

The initial phase of repairs began with a thorough cleaning of the stone surface. Water vapour was chosen as the only permitted method of cleaning. Thus, after almost 150 years, Gloucester’s pride began to slowly lose its grey-and-black robes.

Repairs are currently underway in the oldest part of the cathedral from the “Norman Period”. It was interesting for me that after steam cleaning, the heavily corroded parts of the stone are not removed at all and their future is left to time and nature.

Cement repairs

At the end of the 19th century cement came into fashion in construction. It was added whenever possible. The cathedral didn’t escape it either. The second phase of repairs is the removal of all possible cement mortar fillings. I intentionally use “possible”, but it will be talked about later.

During repairs of historic buildings any intervention in the masonry is inadmissible in our country. But obviously, this was not the case in England 150 years ago.

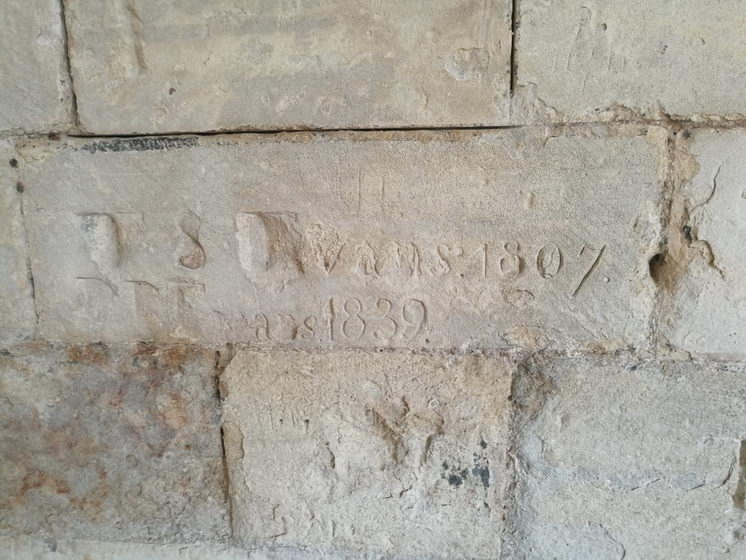

Stonemason’s marks and signatures of cadets

Touching the stonemason´s marks, which were on almost every worked stone, was a very warm feeling on an otherwise cold and rainy day. It had nothing to do with modern graffiti. Every stonemason was paid for each worked piece, and the mark on the stone face made it easier for him to count his work and get paid.

Finally, two small funny facts

During the last repairs, there was a request to extend the windows to better illuminate the interiors of the “Norman part”. The request was met, but in a rather curious way. If you look closely at the following photo, you will find that the extended windows do not have a so-called lining (stone frame) and the stones in the upper arch of the window are held only by the lime mortar.

I used the word “possible” above: in the same photo you can also see the use of cement mortar to neaten the upper arch of the extended window. In this case, the cement mortar will not be removed, as there is a risk of stones coming loose and collapsing from the upper arch of the window.

Source: www.lomyatezba.cz