The secret of basalt faces

More than three thousand years ago, the first great civilisation of Mesoamerica, the Olmecs, developed in the area of the Mexican states of Veracruz and Tabasco.

Their culture is sometimes considered the cradle of all of the following Mesoamerican civilisations. The Olmecs were the first people in this area to found cities and construct buildings here. In this process, they used advanced methods of stone working. They also had very distinctive style in the art of sculpture. The Olmecs knew well how to use many materials, such as clay, basalt, nephrite, or clinkstone. Among their works, you can find stone jewels, sculptures, but also seventeen impressive stone heads. The smallest one weighing six tons.

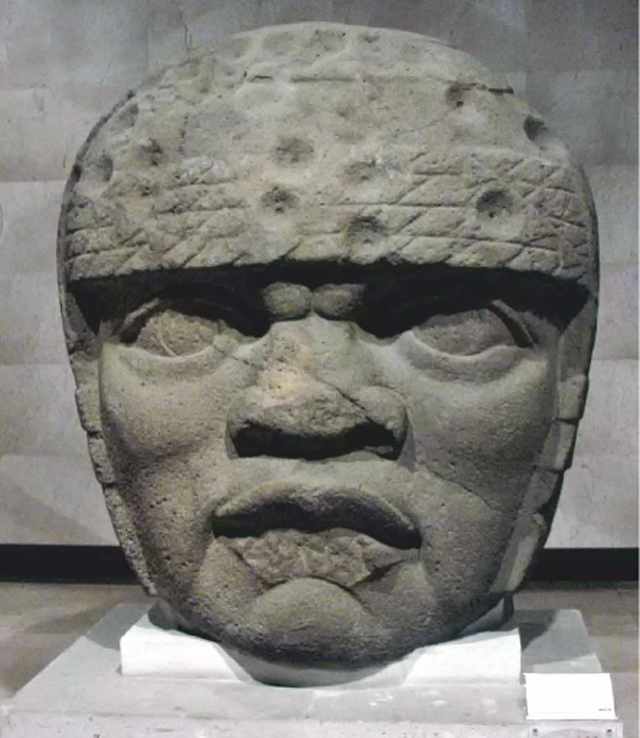

The first stone heads were discovered in the second half of the nineteenth century in three of the biggest city centres of the Olmecs: San Lorenzo, La Venta, and Tres Zapotes. It is difficult to tell their age. Nevertheless, experts agree that they come from the Preclassic Era. This means that the oldest ones are at least three thousand years old. Their height is between 1.5 and 3.5 metres. They weigh from 6 to 50 tons. These giant heads show masculine faces with flattened noses, full lips, and faces. The back part of each head is flat which can mean that they used to lean against walls or laid down on ground staring in the sky. Some of these heads show traces of paint. It is therefore possible that they used to be painted or colourfully ornamented.

Each of the heads is a little bit different. There are differences not only in size, but also in the facial features, facial contours, haircuts, or head covers. Some of them have their hair braided in plaits. Many scientists are convinced that the stone heads are representations of deceased rulers or high priests.

But there are also many other (more or less probable) theories on the motives and function of these stone heads. One of them even says that they represent footballers.

Yes, the Olmecs, and also other cultures of Mesoamerica, knew football. We do not really know the rules or other details but we know that it was a very popular game with elements of a ritual discipline (accompanied for example by human sacrifices to gods). The hypothesis that the heads represent the players, has been largely rejected. It is more probable that the statues depict faces of the rulers getting ready for the game.

There is also another, quite controversial, theory that the stone faces have certain Negroid facial features. This could insinuate possible African origin of the Olmecs. The advocates of this theory are looking for anatomic and genetic similarities as well as possible cultural connections between the Olmecs and aboriginal tribes of Africa, based on early types of writing. But mostly, for insufficient evidence, this theory has been rejected by most of the current scientists.

Another mystery connected to the stone faces from the area of the Mexican Gulf, is the way these giant basalt blocks, the statues are made of, were transported (just a reminder: the heaviest one weighs more than 50,000 kg. Project like this would, without any doubts, require careful planning and employment of tens, maybe even hundreds qualified workers. After research that took many years, it was found out that all the seventeen heads were made of stone that was quarried in the mountains Sierra de los Tuxtlas. That means that the stones had to be transported to the distance of 150 kilometres before they got to their destination. This fact is even more unbelievable if we realize that the old Olmecs did not know the wheel. Although, there are many theories, hypotheses and surmises, it is still unclear how were the Olmecs able to do something like that.

It is possible that we will never be able to solve this or other mysteries that enshroud this ancient Olmec culture. Nevertheless, it is a fact that all of the seventeen heads have been preserved till today and you can see them in Mexico. You can admire them in museums and on special exhibitions.

Source: Kurier Kamieniarski

Author: Jakub Zdańkowski | Published: 2.3. 2016