AN IRISH MUSEUM WITH A POLISH ACCENT 1

fotografie: © Waterford City Council & Philip Lauterbach

There are times when a search for remarkable stone projects yields fruitful results, and there are also times when nothing noteworthy shows up. Sometimes available photographs suggest the usage of stone in some projects, but then it turns out that the building material is a mere imitation of stone. However, there are times when we make a pleasant discovery and come across a true gem.

Such was the case when we stumbled upon an interesting stone façade. Once we started looking for more information, things became even more interesting.

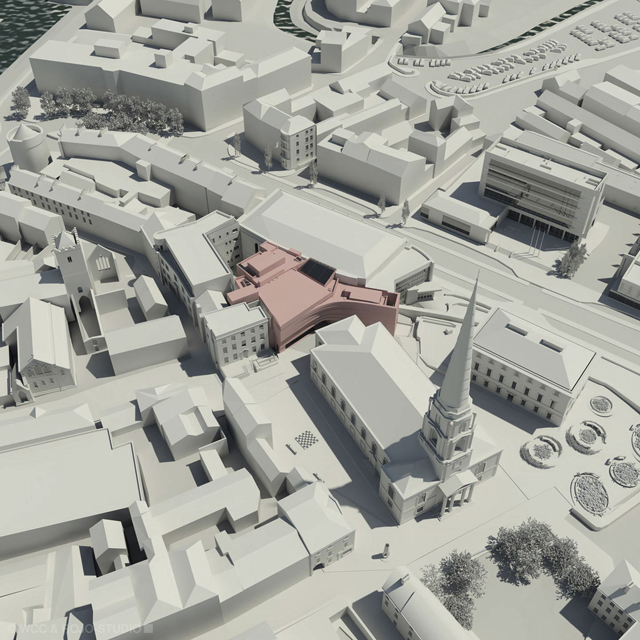

The Medieval Museum in the Irish city of Waterford is located in the oldest part of the city. I was established in 2014 on a site surrounded by buildings dating back to various historical periods: the Middle Ages, the 17th, 19th and 20thcenturies. The space limitation made it rather difficult to design a building that would not just fit in, but also stand as a contrast to the historical buildings surrounding it and become an enriching element.

The shape of the building was given by the shape of the building site. The plot was U-shaped with an open end facing towards the east wall of the Christ Church Cathedral. The front façade is designed in a semicircle that surrounds the back of the neoclassical cathedral and connects two beautiful squares on both sides. As a result, the adjacent part of the city has turned into a bustling cultural centre called the Viking Triangle. The museum organises numerous events for the public, and it features a very interesting collection of ancient artefacts.

The building was designed in 2013 by the city architectural office – an institution similar to the traditional and well-known Polish “city projects”.

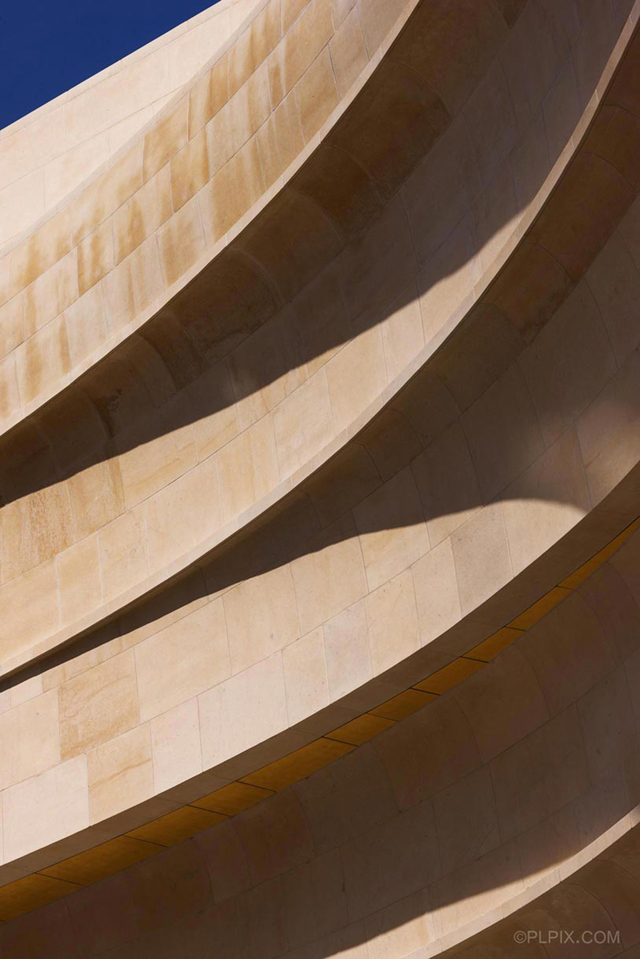

The façade of the building is constructed from the Dundry oolitic limestone that comes from a quarry located on the edge of the northern part of Somerset just a few kilometres south of Bristol in western England. This particular stone was chosen because the same kind of limestone was used in the construction of the adjacent medieval cathedral. Furthermore, the Dundry limestone can be easily shaped to create the effect of breaking the sober and sharp contours of the adjacent 18th century buildings.

The Dundry limestone had been used before in Ireland. It was first brought here in the Anglo-Norman invasion in 1169.

The most famous historical monument in Ireland made of this stone is the Christ Church Cathedral in Dublin. There are many more buildings and monuments in Ireland that are constructed from this limestone.

One might ask why a country so rich in building stone deposits chose to import stone from abroad. The most likely explanation is that some of the stonemasons working on the construction of the local churches were English. The English stonemasons came to Ireland because they had experience with the construction and decoration of large stone churches, which were still a relatively new phenomenon in Ireland at that time. The English stonemasons knew “their” stone very well, and when they came to Ireland, they found out that the local limestone was much harder and therefore more difficult to work. Many of these stonemasons almost certainly came from the west of England, because the architecture of the Christ Church Cathedral in Dublin and other buildings from this period resemble the architectural style we know from the west of England. We can assume that to make their job easier, the stonemasons chose to work with the stone they knew. And that could be the reason why the Dundry limestone can be found on buildings across Ireland.

Let us now go back to the description of the Medieval Museum.

The curved façade looks like a huge jigsaw puzzle – no two stones are the same, each is unique and individual.

Both corners are visible from the adjacent squares. There is a six metres high statue of Our Lady of Waterford carved into the west façade. It is standing on a small 13th century clip found at this site during archaeological excavations.

Upon entering the museum building, the visitors can admire a well-preserved Choristers’ Hall through glass panels. There is a glass wall connecting the ground floor of the building with the cathedral square. This creates the illusion that there is no divide between the building interior and the square.

One of the challenges of the project was to integrate the newly constructed museum building with the medieval architecture of the underground chambers of the Choristers’ Hall. The interior layout of the museum had to respect the topography and location of the neighbouring buildings.

The building has four floors. On the ground floor there is an entrance area, the museum gift shop, and reception. On the second floor there is an exhibition gallery and audio-visual halls. On the lower ground floor there is a multipurpose space that opens to the Choristers’ Halls.

The structure of the building is concrete. The materials used in the construction are concrete, Irish Pippy Oak, Welsh slate, and the aforementioned Dundry limestone.

In 2014 the museum won a number of awards, including the LAMA Awards in the categories “Best Public Building” and “Best Heritage Project”, as well as the International Civic Trust Award. This outstanding achievement is the result of cooperation of people from various areas: architects, artists, historians, engineers, and craftsmen, who all contributed to the realisation of this unique project.

And finally, the most interesting information: the museum was designed by Polish architects Bartosz and Agnieszka Rojowski, and the city architect Rupert Maddock. We found this finding most intriguing, which is why we contacted the architects and asked them about their path to the project and its realisation.

Source: Kurier kamieniarski

Author: Dariusz Wawrzynkiewicz | Published: 03 July 2019